The O. Henry Prize-winning author of Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts and Perfect Black will visit Shreveport in October

by Chris Jay

This site is funded by tips from readers. Support Chris with a tip of $5 or more using the link below.

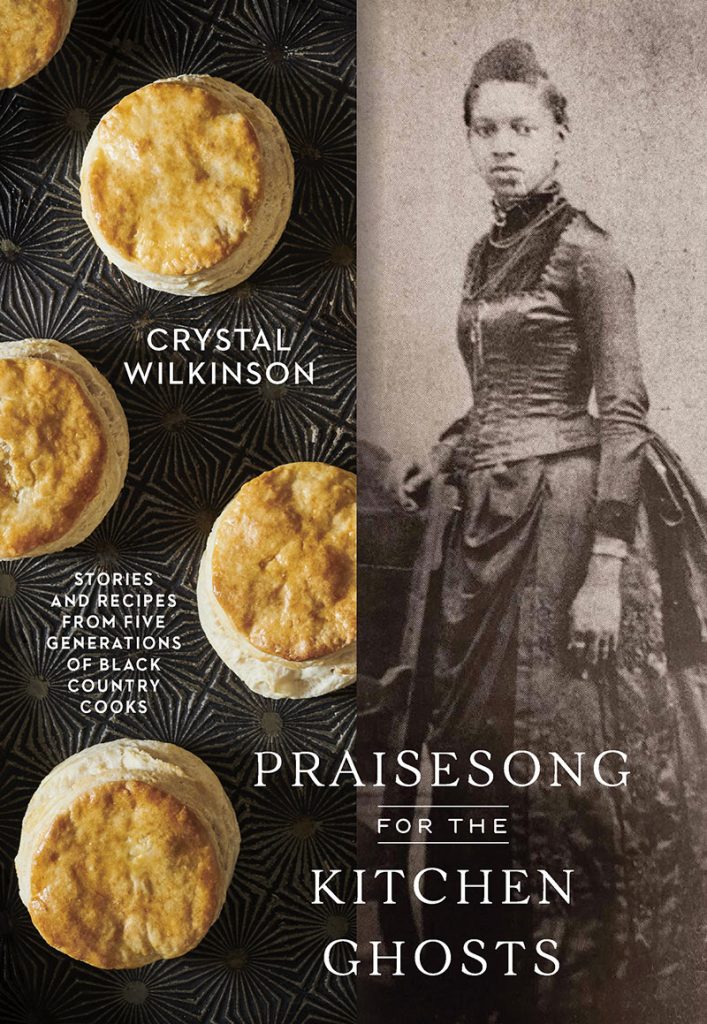

Centenary College’s 2025 John William Corrington Award for Literary Excellence will go to Crystal Wilkinson. According to her awe-inspiring bio, Wilkinson is a past recipient of the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Poetry, the O. Henry Prize, an Academy of American Poets Fellowship, a USA Artists Fellowship, and the Ernest J. Gaines Prize for Literary Excellence. She has also served as Poet Laureate of Kentucky. Her new cookbook, Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts, is a national bestseller that interweaves family memoir, prose, and recipes in a way that has been compared to the culinary memoirs of Edna Lewis. Wilkinson will present a reading and accept the Corrington Award during a public ceremony held at Marjorie Lyons Playhouse on Monday, Oct. 27, 2025.

I’m reading Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts now, and I can honestly say that I’ve never read anything like it. The closest comparison that I can draw is to The Taste of Country Cooking, Lewis’s genre-defining culinary memoir that feels intimate, free-wheeling, and poetic. Where Lewis embedded readers in a rural Virginia farming community founded by freed slaves, Wilkinson immerses readers in the lives, barns, gardens, and kitchens of Black Appalachians in eastern Kentucky.

In Louisiana, some of the traditional Black Appalachian recipes featured in Praisesong will be immediately recognizable as examples of capital-S “Southern” cuisine (chess pie, blackberry jam, biscuits), while others may seem new and different (hot milk cake, sauteed fiddleheads, turkey hash). That may be why I enjoy the book so much: The foods found in Wilkinson’s South diverge just enough from mainstream imagery of Southern cooking that they feel both familiar and totally new.

The way that Wilkinson’s text shifts, without warning, from a narrative memoir of living off the land to a block of recipes—only to snap back into the shape a narrative, or weave unexpectedly into a poem or photo of an ancestor’s dress—is fun for the reader. Lots of chefs have dedicated pages of their cookbooks to memories of the people and places that inform specific culinary traditions, but Wilkinson pushes further into the intimate territory of a close family than I can ever recall having gone in the pages of a cookbook.

It’s undeniably exciting that Wilkinson is going to be spending time in Shreveport. With any luck, she’ll get to know kindred spirits like Hardette Harris, of Us Up North Kitchen, and Panderina Soumas, of Soumas Heritage Creole Creations, who have done extraordinary work exploring the idea of recipes as family memoirs. Maybe she’ll forge friendships within the local Slow Food community, as so many other visiting food writers have. I’m curious to know what Crystal Wilkinson sees when she looks at Shreveport.

Portrait of the author courtesy of Carsen Bryant

Book image courtesy of Clarkson Potter Publishers